In November 2022, Li Ying, a young artist and recent graduate from an art academy in Milan, found himself trapped in sorrow, fear, and despair. Strict pandemic controls in China meant three years without seeing his parents, unsure of his country’s future.

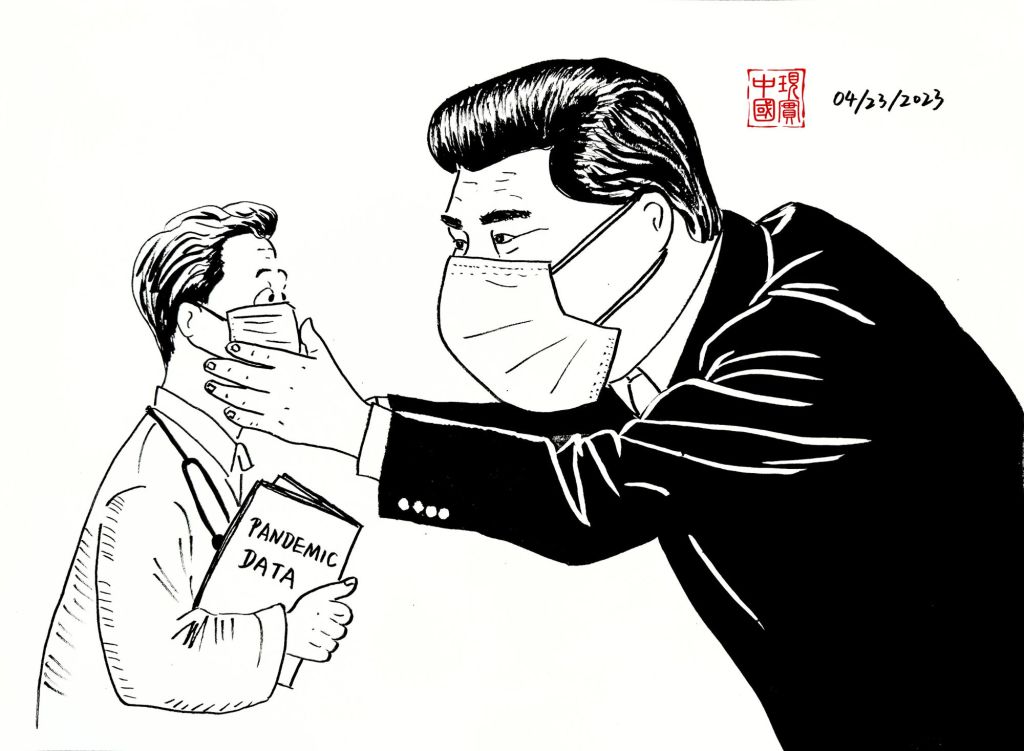

In China, enduring endless COVID-19 tests, isolation, and lockdowns, people staged the most widespread protests in decades. Many held up A4 sheets of paper in defiance of censorship and authoritarian rule—the White Paper Movement.

Unexpectedly, Li transformed his Twitter account into an information hub, receiving censored photos, videos, and eyewitness accounts from within China, disseminating them globally via the platform. His profile picture—a cute yet fierce cat he painted—quickly became iconic.

Within weeks, his followers grew to half a million. To the Chinese government, he became a troublemaker; to many, a superhero against Xi Jinping’s regime.

As the government abruptly ended pandemic policies in December, Li and other activists faced a pivotal question: was their protest a historic moment or just a footnote?

Li reflected, “The White Paper—it’s a beginning, not an end.” He evolved from a young artist to a rebellious internet figure, navigating fear, guilt, courage, and hope. For many peers, this path is all too familiar.

At 31, Li Ying is part of a generation of young Chinese activists driven by a sense of justice and dignity, standing up against the government and Xi Jinping. They are not professional revolutionaries but have become activists by necessity, as Xi turns their country into a massive prison and their future into a black hole, compelling them to speak out.

They face the consequences, some within China, others abroad. They are arrested, harassed by police, or forced into exile out of fear of government threats. As more people join their resistance, their activism continues.

Li Ying never intended to be a hero. Over the past year, he has paid a heavy personal price. Sometimes, he cried, wanting to give up. But the government’s relentless punishment left him no choice but to keep moving forward.

Returning to China is too risky for him. Police often harass his parents. All his bank accounts, payment methods, and even gaming accounts in China have been frozen. He lost his only source of income in Milan, where he has been studying and living since 2015; he says this is because the company he worked with received a letter from the Chinese embassy. He receives death threats almost weekly. A man once broke into his residence, an address Li Ying says only the Chinese consulate knew. For safety, Li Ying has moved four times in the past year.

Li’s dedication to his cause is unwavering, driven by love for his country and its people. Despite personal risks and sacrifices, he persists, knowing there’s no turning back.

He remains a lifeline for Chinese seeking uncensored news, a testament to the cracks in China’s Great Firewall and the resilience of those striving for change.